WARNING

You are viewing an older version of the Yalebooks website. Please visit out new website with more updated information and a better user experience: https://www.yalebooks.com

Yale Margellos

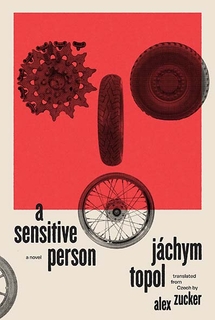

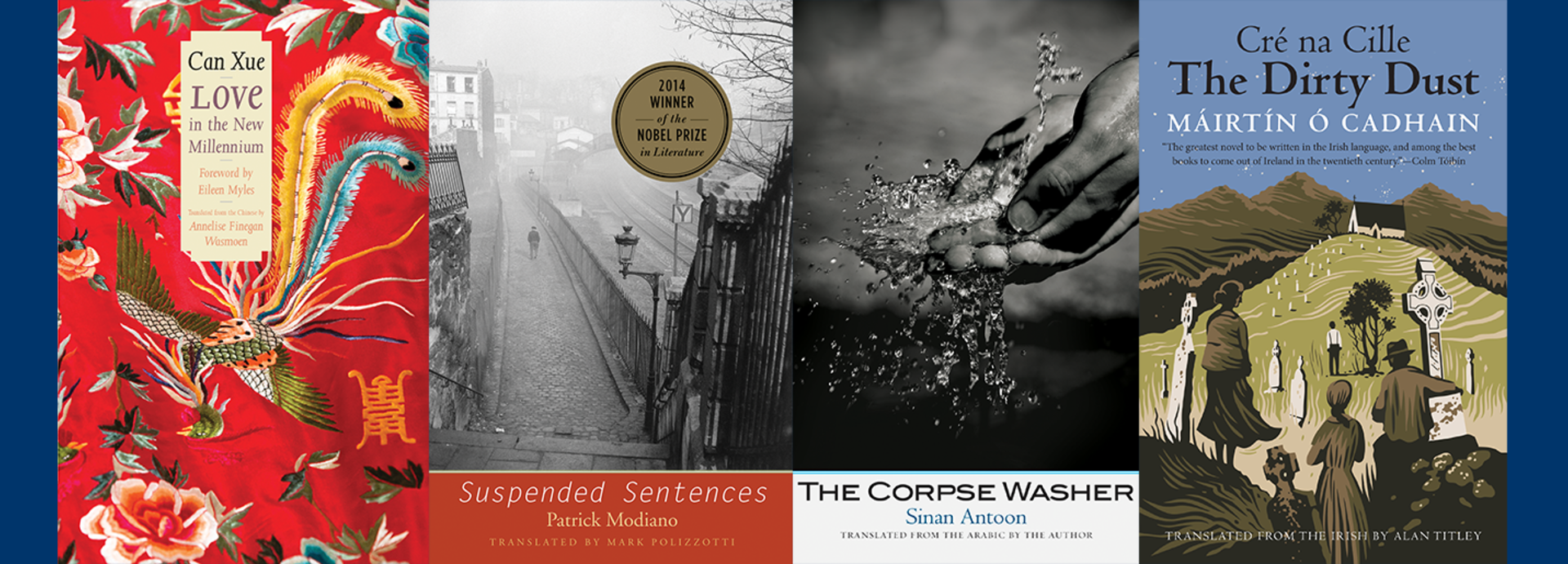

The Cecile and Theodore Margellos World Republic of Letters series identifies works of cultural and artistic significance previously overlooked by translators and publishers, as well as important contemporary authors whose work has not yet been translated into English.

New Releases

Serhiy Zhadan; Translated from the Ukrainian by Reilly Costigan-Humes and Isaac Stackhouse Wheeler

Antonio Lobo Antunes; Translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa

Cees Nooteboom; Translated from the Dutch by Laura Watkinson; With Photographs by Simone Sassen

Web Exclusives

Montevideo is a metafictional tale, by premier Spanish author Enrique Vila-Matas, that explores the limits and possibilities of literature. In this Q&A, translators Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott discuss the author’s writing style and the process of co-translation.

What particular translation challenges arose as you brought Vila-Matas’s Montevideo into English?

SH: The British novelist Adam Thirlwell described Vila-Matas’s writing style as a kind of “textual delirium” marked by “an array of quotation, plagiarism, frames, self-plagiarism, digressions and meta-digressions.” Constantly tracking down quotes or references only to discover that a character has misremembered or deliberately misrepresented or misappropriated them is surely every sane literary translator’s nightmare! But to us, these quests were actually delicious and delightful follies, which reminded us that serious literature doesn’t have to be serious. Great fiction needn’t lead to great revelations—actually, it can send you round the houses on a quixotic but far more enlightening journey through ideas that make no pretense of leading to a definitive conclusion, or to some essential truth. Novels that do that are easier to translate, but they reduce reality to something neat, which feels far from truthful when, in fact, the stories that make up a life are winding. The minds that construct narratives are messy. Translating Montevideo involved an awful lot of research and debate on our part as translators, but for us as much as for, we hope, any future reader of this playful, honest, intelligent novel, Ithaca was the journey . . .

Explain how this novel came to be a co-translation. What were the benefits of collaborating on this story?

SH: I was approached to translate Vila-Matas because Margaret Jull Costa couldn’t do it, and she kindly recommended me. It was actually another book, called Esta bruma insensata, that I was commissioned to translate, and I had recently read Annie’s review of that novel in the Times Literary Supplement. Her reading chimed so closely with my own that it seemed the ideal book to work on together. I think Annie is one of the best translators working today, and I knew I would learn a lot from tackling a difficult Vila-Matas novel with her. In the end there was a schedule change, and the book we ended up doing for Yale became Montevideo.

As to the benefits of co-translating, it’s always advantageous to have two sets of eyes on a translation—conversation is generative, so you gather a wider range of possible solutions, dismiss many, defend others, and slowly whittle it down to “the one.” Co-translated copy is cleaner, because it’s been read by more than one translator, and crisper, for the same reason, and in the case of Vila-Matas and this novel more specifically, the jokes land better, because they’ve been tested already. Vila-Matas has a unique sense of humour—he is at once wry, silly, slapstick, absurdist, deadpan. Producing the right tone or word combination to make the text funny in English was facilitated by working together—it was a bit of a comedy writers’ room situation.

How did you incorporate the narrator’s inner conflict throughout the novel into the translation?

AM: One of the first conversations when we began translating was about this very thing. Here’s how the novel begins: “In February of ’74 I traveled to Paris with the anachronistic intention of becoming a writer from the 1920s, ‘lost generation’ style. That was my, shall we say, unusual aim on moving there.” There was much discussion of that “shall we say”: would it not, we wondered, be neater to go for “somewhat unusual” and be done with it? But no: the narrator’s not simply saying that his intentions could be described as unusual, but that describing them as unusual would be kinder than they deserve: they’re really pretentious, perhaps, or self-absorbed, or filled with delusions of grandeur. Already, in the opening sentences of the novel, there are layers of irony and self-awareness that we as translators had to be sensitive to, and that set the tone for the rest of our translation.

In a previous interview, you (McDermott) stated that “I think books kind of teach you how to translate them, the more time you spend with them.” What unexpected realizations did you have while working on this novel?

AM: It was a great lesson in dealing with uncertainty, and in translation as exploration, as a kind of literary quest. Often, I find I need to determine exactly what’s happening in a sentence before I can re-create it in English—if I don’t know what I’m meant to be saying, how can I say anything at all? The writing and thinking in Montevideo, however, wind so sinuously and idiosyncratically from idea to idea that at first I felt quite paralyzed—it seemed impenetrable! Or perhaps not impenetrable—Vila-Matas, with his usual wit and warmth, was very much inviting us in, but what we’d been so genially welcomed into was a sort of literary labyrinth, a maze of hotel corridors lined with locked doors, secret doors, doors that disappeared overnight, and the only way out was through. There was nothing for it but to follow Vila-Matas down these winding passageways, trusting that he knew what he was about even if we didn’t yet, discussing what adjective would best fit a frog dangling on a thread from a celebrated critic’s lapel before being quite sure why the frog was there. (“Filipendulous,” we decided. It was a filipendulous frog.)

With each successive draft, we moved deeper into Montevideo’s world, spotting more connections, hearing more echoes, laughing at more jokes, and sharing more revelations. And the translation process, from its slow beginnings, became one of the most creative I’ve known, fizzing with flashes of inspiration, linguistic flourishes, and neat solutions to tricky conundrums. It was a lesson, in a way, in trusting a book—if reading is about going on a journey with the author, then so too is translation.

When reflecting on what made you (Hughes) want to become a translator, you stated that “Translations weren’t next-best things. The translator was a writer. I wanted to have a go.” Discuss the similarities between authorship and translation as literary art forms.

SH: Funnily enough, it is a line quoted by Annie in a recent interview that encapsulates my thoughts on this. She referred to Nabokov’s idea of translation as “‘pure writing’: dealing entirely with the words themselves, while someone else takes care of the characters and plot.” That’s pretty much it. There isn’t a hierarchy; we’re doing different jobs. Authors do plenty of pure writing, too, because when they aren’t dealing with characters and plot, there is style, aesthetics, and language to attend to. And translators, unlike authors, pull off a kind of pure writing that involves a particular set of constraints or prompts. We follow a score, remaining attentive to the author’s style, aesthetics, and language, as opposed to whatever might have come from our own head were we authoring the book. The thing that doesn’t differ between translating and writing is that the more drafts you produce, the better the result will be.

The two of you worked together in 2024 to co-translate Layla Martinez’s Woodworm. How would you say your relationship as collaborators evolved from one project to the next?

AM: It’s a good question, and one that’s tricky to answer because our relationship as co-translators felt seamless from the start—it’s such a luxury to work with someone you trust so much and see eye to eye with on so many things. The trust has always been there, but by the time we were working on Montevideo it felt almost total.

Our process was to share out the chapters of the book and each produce an initial draft of half of them, and then send each chapter back and forth between us for editing until it felt done (and then, inevitably, a few more times after that). It was always so exciting to see an email pop up from Sophie with her edits on a chapter, and I’d drop everything to open it and see what she’d done—which was normally exactly what I wished I could have done, neatly solving all the dilemmas that had been plaguing me and that I’d highlighted with a comment in the margin containing something highly articulate like “Argh!” When we began work on Woodworm, we were communicating by email; by the time we put the finishing touches to Montevideo, we weresitting in my kitchen eating soup in a rainstorm: beginning to translate together was also the beginning of a great friendship.

Enrique Vila-Matas (b. 1948) is an acclaimed Spanish novelist, critic, filmmaker, and journalist. He is the author of numerous novels, stories, and essay collections, and his works have been translated into more than thirty languages. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott have translated some fifty books from Spanish and together were nominated for the 2024 National Book Award in Translation.

The post Montevideo: A Conversation with Sophie Hughes and Anne McDermott appeared first on Yale University Press.

Featured Translators

Contact Us

For any questions regarding the Yale Margellos, please use the button below to contact us.